In this first blogpost of our SkyNRG Thought Leadership Series we dive deep into the impacts of ReFuelEU, taking the perspective of fuel suppliers, airports, aircraft operators and corporate travellers. Looking ahead in time, we also make suggestions for improvement of the regulation.

More insights on the development and the trends of the Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) market can be found in our SAF Market Outlook.

Introduction

On 9 October 2023, the European Council formally approved both the ReFuelEU and the RED-III legislative texts. After years of intense discussions, the EU-bloc can now be proud of having passed the most comprehensive framework in the world yet, aimed at stimulating sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) supply while simultaneously protecting the EU level playing field.

Exactly this strong focus on the level playing field is what makes ReFuelEU different from the design of other policies in “Fit for 55”. Given the international character of aviation, the EU requires that a harmonized set of rules be applied to all fuel suppliers, airports and aircraft operators in the Union. This has led to an approach where not the member states, nor the airlines, but the fuel suppliers have to comply with SAF blending targets, even though they might supply aviation fuel across country borders.

A set of harmonized rules across the EU also means that member states are not allowed to put in place national mandates that supersede ReFuelEU. Specifically, the Dutch blending mandate of 14% by 2030 and the German PtL quota of 0.5% in 2026 and 1% in 2028 would have to be scrapped. Instead, member states would have to look for ways to motivate fuel suppliers to blend more SAF through incentives, e.g. via the RED-III which also has aviation in scope. Voluntary markets can also trigger additional supply in countries where incentives are available.

Obligations

Fuel Suppliers

Fuel suppliers are required to deliver minimum blends of SAF and synthetic aviation fuel to Union airports in scope (see Airports). Starting in 2025, a blending target of 2% SAF applies, increasing to 70% SAF in 2050 (Table 1). Minimum shares increase in discrete steps, whereas sub-targets for synthetic aviation fuel between 2030 and 2035 have defined averages and minimum shares. This means that fuel suppliers can fall short of the sub-target and compensate a year later.

Targets for 2025 and 2030 seem to be feasible when assessing SAF capacity announcements in Europe.

Table 1: Minimum shares of SAF to be delivered to EU airports by fuel suppliers

Today, we identify a gap of 0.9 – 2.0 Mt SAF in 2030 between announced capacity in Europe and what is needed to meet mandates in the EU and UK, depending on aviation fuel demand in 2030. This gap can be met through additional announcements in coming years and imports from outside of Europe.

Airports

Union airports are all airports with a passenger traffic of ≥ 800,000 per year or ≥ 100,000 tonnes freight throughput. Airports in ‘outermost regions’ are excluded. Airports in scope are expected to cover roughly 95% of all EU aviation traffic.

Airports are required to facilitate access to SAF by the time the physical supply obligation kicks in for fuel suppliers in 2035 (see Flexibility Period). Through airport incentives, airports can also make it more attractive for fuel suppliers to supply at certain airports, though this is not required by ReFuelEU.

Aircraft operators

Aircraft operators are required by ReFuelEU to uplift a minimum of 90% of their annual aviation fuel needs from EU airports within scope. This obligation serves as an anti-tankering1 measure and applies to commercial airlines and all-cargo flights, with exceptions applying. The uplifting obligation for aviation fuel effectively ensures that airlines consume the SAF blends that suppliers will be required to deliver. To have a strong market position, aircraft operators can negotiate attractive long-term offtakes with producers and have this supplied to them via fuel suppliers.

This anti-tankering measure technically does not prevent aircraft operators to stop for refueling in the UK, Switzerland or Turkey on long-distance intercontinental routes, since ReFuelEU does not apply to those countries. However, discussions on SAF mandates in these countries are also taking shape, so this may soon no longer be a risk.

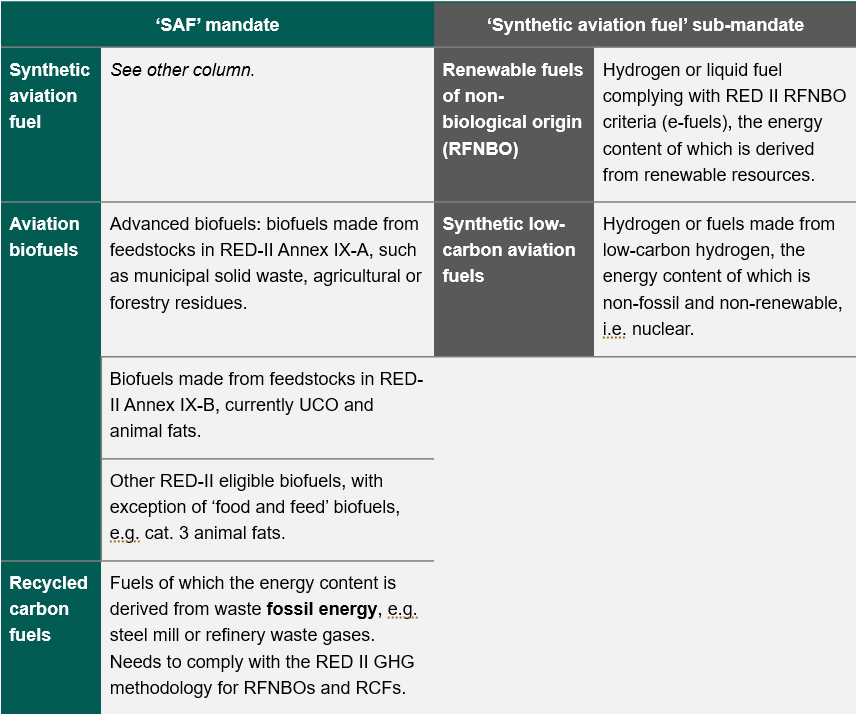

Eligible SAF

Compliance with the minimum shares under ReFuelEU can be achieved with different types of SAF (Table 2). Fuel made from intermediate crops, palm and soy-derived materials and soap stock and its derivates are excluded, unless the feedstocks appear on the list of eligible feedstocks (Annex IX) of the Renewable Energy Directive (RED). A proposal amending Annex IX is currently being considered and could see intermediate crops added under certain conditions, as well as other feedstocks. Relatively late in the ReFuelEU negotiation process, a final category was added: ‘synthetic low-carbon aviation fuels’. Championed by France, these are fuels made with non-fossil, non-renewable energy, thereby indirectly referring to nuclear power. A delegated act under the forthcoming Gas Directive will specify the GHG methodology for this category of fuels.

Table 2: Eligible types of SAF under the ReFuelEU SAF mandate and the synthetic aviation fuel sub-mandate

Flexibility period

From 1 January 2025 until 31 December 2034, aviation fuel suppliers have the flexibility to average supplies of SAF to Union airports for compliance with the minimum shares. This means that fuel suppliers can choose to supply all their SAF at one or more of the airports they supply, if that is logistically more attractive. Since fuel suppliers located in one member state often supply aviation fuel across borders, this could also mean that the average share of SAF in some countries will be higher or lower compared to the minimum shares in ReFuelEU. This is further influenced by the availability of airport incentives for SAF, such as those at Schiphol Airport.

Being able to average out supplies, while convenient for fuel suppliers, does give rise to a mismatch between ReFuelEU and the EU’s Aviation Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS). If aircraft operators want to use the SAF they purchased to contribute to reducing the amount of carbon allowances they need to surrender, SAF needs to be physically supplied to the airport and allocated to specific flights. With the flexibility mechanism in place, aircraft operators that want to claim ‘ReFuelEU SAF’ under EU ETS will have to negotiate offtakes to ensure the SAF physically enters the airport fuel system. Revisions to EU ETS monitoring, reporting and verification protocols may also address this issue. However, in the meantime some airlines may be able to claim SAF use under the UK ETS, which does not have the same requirements on physical supply as EU ETS.

Physical deliveries of SAF may be further influenced by the ETS SAF allowances programme, which also has a requirement on physical delivery and allocation to flights (see SAF Allowances).

Supply dynamics are further complicated by airline ambitions to uplift more SAF than the mandated minimum shares on a voluntary basis. In practice, this could lead to a reduced obligation for fuel suppliers and reduced fuel costs for competing aircraft operators.

The ReFuelEU flexibility mechanism will most likely not lead to situations where the ASTM blending limit of 50% SAF is reached, as the supply of SAF will most likely be concentrated at a few airports that are supplied via underground pipeline networks. Transport via pipeline is not only more cost effective, but the quantity of SAF will also be diluted by the fossil jet fuel supplied through the same system.

Penalties

What makes ReFuelEU stand out compared to other countries with SAF targets are the stringent penalties for non-compliance. Different from a buy-out price in which you can buy yourself out of the obligation as a fuel supplier, suppliers and aircraft operators under ReFuelEU are faced with a penalty but still need to make up for their non-compliance in the following year. National authorities are tasked with overseeing compliance of aircraft operators and fuel suppliers. Income from penalties are required to be earmarked for funds that support SAF projects.

Fuel Suppliers

Failing to comply with the minimum shares of SAF means fuel suppliers are liable to pay a fine of at least twice the difference between the price of conventional aviation fuel and SAF in that year. The European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) is tasked with collecting market intelligence on SAF pricing every year.

Example: Jet-A1 price €600/mt. SAF €3,500/mt.2 Difference multiplied by two is €5,800.

The question remains as to how market prices for SAF and synthetic aviation fuel will be established given that actual pricing is often confidential. EASA may have to rely on spot indicators developed by the likes of Argus and Platts. In addition to the fine for non-compliance with the minimum shares, the same fine also applies for fuel suppliers that report inaccurate information regarding the characteristics or the origin of SAF. An important prerequisite for this non-compliance mechanism is that supply of SAF is available. If not, this mechanism could lead to investments in converting renewable diesel production to SAF as the road sector does not have such stringent non-compliance penalties.

Aircraft operators

Failing to meet the 90% uplift obligation results in a fine of twice the price of conventional aviation fuel for the amount of fuel the aircraft operator failed to tank relative to the obligation. Because aircraft operators have no SAF uplifting obligation, the price of the fine is not linked to the price of SAF.

SAF Allowances

From 1 January 2024 until 31 December 2030, 20 million carbon allowances from the Aviation ETS will be reserved to finance SAF use by ETS-eligible aircraft operators. This means that SAF allowances can only be used on intra-EU flights, representing about 40% of total aviation fuel use in the EU.3 All SAF under ReFuelEU could therefore be allocated to intra-EU flights well into the 2040s. While first proposed as a part of the ReFuelEU proposal, the SAF allowance program is now a part of the Aviation ETS.

Carbon allowances are taken out of the pool of total allowances that are available for aviation and are allocated to airlines using SAF, operating in the form of a contracts for difference (CfD) scheme to cover the price differential between conventional aviation fuel and SAF. The price of avoided ETS carbon allowances is subtracted from this price differential. SAF allowances are allocated to cover different parts of the price differential, depending on the type of fuel used and where is it used:

- Advanced biofuels and renewable hydrogen: 70%

- Renewable fuels of non-biological origin (RFNBOs): 95%

- SAF used at airports that are not classified as Union airports in the context of ReFuelEU or airports on remote islands: 100%

- Other eligible SAF (e.g. SAF made from UCO or animal fats): 50%

Example: Jet-A1 price €600/mt. SAF (UCO-based) €3,500/mt.4 ETS allowance price €100/tCO2. Avoided carbon costs for conventional aviation fuel at 3.15 tCO2 / t fuel * €100 €/tCO2: €315/mt SAF. €2,900 minus €315: €2,585 * 50% = €1,292.50. SAF allowances should be allocated to cover €1,292,50 per tonne of UCO-SAF in this case. At a price of €100 per allowance this is ~13 ETS allowances.

Taking the example above for ‘other SAF’, which will be the dominant type of SAF for the duration of the SAF allowance scheme based on SAF production capacity announcements worldwide, 20 million allowances would be able to fund 50% of the differential for about 1.5 Mt of SAF. Estimated mandated supply of SAF under ReFuelEU between 2025 and 2031 is ~8 Mt. This SAF allowance scheme could therefore cover a significant part of the price gap for close to 20% of SAF under the mandate, on a first-come, first-served basis.

While this scheme is welcomed by airlines and freight forwarders with ETS obligations, the scheme provides limited additional investment certainty for fuel suppliers. This is because aircraft operators will have to apply for funding at the national authorities every year, subject to availability of allowances. Clarity on the extension of this scheme beyond 2031 could reduce uncertainty for investors.

Non-CO2 reporting

Both aircraft operators and fuel suppliers will experience substantially increased levels of reporting. Fuel suppliers will have to use the Union database5 to report on a range of supply and sustainability characteristics. Worth highlighting is the reporting requirement on aromatics and naphthalene content, known to be a driver of non-CO2 impacts of aviation. This reporting requirement is seen by the industry as a potential precursor to the inclusion of aviation’s non-CO2 effects into a carbon pricing scheme.

Book and Claim

Over 50% of aviation fuel in Europe is consumed at just ten airports. Having to supply all Union airports with a SAF blend is expected to add to the cost of SAF. Logistics are responsible for most of this added cost, for instance because blending locations are often not located near SAF production locations and airports, but rather at fuel storage terminals. This means that supplying relatively small batches of SAF involves additional costs compared to existing large-scale supply chains of conventional jet fuel. Primarily for EU airports that are not connected by pipeline, ReFuelEU compliance costs could be reduced throughout the flexibility period with a ‘book and claim’-like system. This would enable fuel suppliers to supply SAF to airports via pipeline delivery and trade excess credits to fuel suppliers with supply deficits.

Because of the highlighted reasons, the European Commission is considering such a book and claim system and will present a report to Parliament and Council by 1st July 2024. Naturally, a European registry for such credits linked to the Union Database would have to be developed that can mitigate the risk of double claiming.

However, this should go hand-in-hand with the possibility for aircraft operators to claim SAF under EU ETS on the basis of purchase records. Otherwise, this system would disadvantage carriers operating from regional airports.

Policy recommendations

By 1 January 2027, and every four years thereafter, the Commission will present a report on the functioning of ReFuelEU and possible improvements. Below, we make a number of suggestions for improvement to ReFuelEU:

- Introduce a sub-target for advanced biofuels.

ReFuelEU mandates will be met with the least-cost SAF available on the market that is compliant with the SAF criteria. However, to meet SAF supply targets beyond 2030, SAFs will be needed that cannot compete with waste oil-based SAF today. This is recognized in the RED III, where fuels made from ‘advanced’ feedstocks, e.g. agricultural or forestry residues, have a sub-target. ReFuelEU does not have this. To provide the necessary investment signals to the sector, a sub-target for advanced bio-based SAFs should be introduced by 2030. - Extend the SAF allowances program to 2040 to provide investment certainty for fuel suppliers.

Currently, SAF allowances are only available until 2031 on a first-come, first-served basis. This mainly helps airlines purchase waste oil-based SAF, as limited amounts of advanced SAF and e-fuels will be available until 2031. Extending the program until 2040 will provide more confidence to investors in SAF production capacity. - Provide more flexibility to member states wishing to set more ambitious targets on SAF supply.

To protect the EU level-playing field for aviation, the Commission does not allow for the implementation of national mandates. This unfortunately puts the brake on potential SAF supplies in the EU and progress towards net-zero emissions in aviation. Impact on the level-playing field can be limited if member states were allowed to set targets for aviation sector emission reduction under the RED, with flexibilities on which transport sector to allocate the financial burden to. - Develop a European book and claim registry for SAF under ReFuelEU.

For the reasons stated above.

Concluding notes

While there is always room for improvement, ReFuelEU does provide the final set of rules the industry so desperately needed. Now that the rules are agreed, the specifics of implementation need to be detailed out in the next few months in preparation for 1 January 2025, as a number of things are still unclear. Also, we need to make sure that the SAF capacity that is announced to date materializes and is not delayed as a result of inflationary pressures, permitting issues and volatile financial markets. The ambitious targets laid out under ReFuelEU require of us to de-risk new technologies faster than ever before. The investment challenge will be huge, €250 billion in CAPEX to meet 2050 supplies under ReFuelEU alone. However, this represents a mere 2% of global annual upstream oil and gas CAPEX, signalling that the funds are available, but we need to direct it to the right pathways and demonstrate that it makes financial sense. Corporates with bold climate ambitions can further help de-risk investments, for example by engaging in offtakes for Scope 3 environmental attributes. At SkyNRG, we aim to connect policy makers, investors, aircraft operators and corporates to scale SAF.

1Tankering is the practice of uplifting more fuel than is needed for the subsequent flight. Due to fuel price differences between airports, airlines may choose to take on more fuel at airports with low fuel prices, in order to reduce the amount they would need to refuel at airports with higher fuel prices. From a CO2 emissions standpoint, this can be seen as an undesirable practice, due to the airplane being heavier during flight.

2 Illustrative pricing.

3 EEA, 2023. European Aviation Environmental Report

4 Illustrative pricing.

5 The Union Database, when operational, will also be used for compliance under the EU RED.

Published on 24/11/2023

Would you like to know more?

You must be logged in to post a comment.